Reflecting on President Trump’s first 100 days in office

Search

Search

Search

Search

In July 2024, the Intellectual Property Enterprise Court handed down judgment in a trade mark and copyright infringement case between AGA Rangemaster Group, the manufacturer of the well-known AGA range cookers, and UK Innovations Group, a company selling second-hand AGA cookers which had been converted to run on electricity. In this article, we examine the key takeaways from this decision, including (1) the limits of the exhaustion defence to trade mark infringement, (2) the boundary between copyright and design protection under UK law (and potential divergence with EU jurisprudence post-Brexit), and (3) the application of accessory liability principles to company directors following the Supreme Court's pivotal decision in Lifestyle Equities v Ahmed.

The claimant, AGA, has manufactured and sold variations of its famous AGA range cookers in the UK since the 1920s, many of which have been operating for decades. The defendants, UKIG and its director, Mr McGinley, had developed a system to convert existing AGA cookers to run on electricity rather than fossil fuels (the "eControl system"), which it both sold to existing AGA cooker owners and retrofitted to pre-owned AGA cookers it secured in the secondary market and then sold on ("eControl cookers").

AGA sued the defendants for trade mark and copyright infringement. It was common ground between the parties that there is a sizeable repair, refurbishment, and resale market for AGA cookers given their long use life. UKIG's eControl cookers retained their AGA logo and looked externally similar to AGA cookers; the only visual difference was that UKIG replaced the now redundant temperature gauge with an eControl System badge.

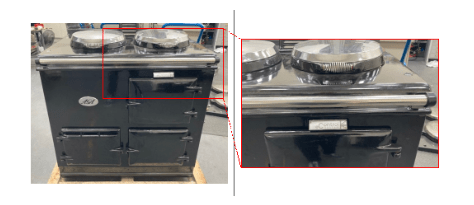

An eControl cooker; The eControl badge is highlighted in the right-hand picture.

AGA acknowledged that its products may be sold on in this secondary market, but it argued that UKIG had altered its products in such a way that AGA had a legitimate reason to oppose UKIG's sale of the retrofitted cookers which had been fitted with the eControl System.

Accordingly, AGA claimed:

AGA relied on its trade mark registrations in:

which were registered for (among other goods) cooking apparatus, ovens, cookers and stoves.

Given UKIG's use of the identical sign AGA in its marketing and its sale of eControl cookers bearing the AGA badge, the court found that UKIG had infringed the word marks and logo mark under section 10(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 ("TMA"). AGA's 2D and 3D marks were infringed under sections 10(1) and 10(2) TMA by UKIG's use of images of the eControl cookers and also the eControl cookers themselves, which the average consumer would perceive as either identical or highly similar to the relevant marks. The court held that UKIG's use of the signs in question also took unfair advantage of the distinctive character of AGA's trade marks without due cause under section 10(3) TMA.

UKIG nonetheless sought to rely on section 12 TMA, which provides a defence to infringement where a trade mark proprietor's rights have been "exhausted" by the sale of goods in the UK or EEA under their mark and with their consent. However, alleged infringers cannot avail themselves of this defence where there are legitimate reasons for the proprietor to oppose further dealings in the goods, for example, where the condition of the goods has been changed or impaired after they have been put on the market (s.12(2)(a) TMA).

Given the long-lasting nature of AGA cookers and consumers’ expectations as to the quality of repaired and retrofitted products of this kind, the court concluded that AGA did not have legitimate reasons to oppose UKIG’s selling of refurbished AGA cookers per se. Purchasers of eControl Cookers would expect such models to be fitted with replacement parts that are not of the exact quality of those used in an AGA cooker; therefore, the use of replacement parts would not diminish the reputation of AGA cookers. Moreover, UKIG’s retrofitting of the eControl System to AGA cookers did not impair their quality.

However, the court held that AGA did have a legitimate reason to object to how UKIG marketed the eControl cookers. Statements such as "Buy an eControl AGA" and references to "AGA eControl" in invoices suggested that UKIG had a commercial relationship, or at the very least, a connection with AGA. In circumstances where AGA's own electric cooker models were marketed under names like "AGA eR7" and "AGA Deluxe", there was a risk that consumers would believe the eControl cookers to be linked to AGA's brand.

The section 12 defence requires the court to strike a fair balance between the need to protect the trade mark proprietor’s interests where its mark is applied to goods, and the interests of the original purchaser and others who deal with the goods in the aftermarket. In the present case, UKIG was deemed to have unfairly sought to give the impression of a commercial relationship between itself and AGA, tipping the balance in AGA's favour. The court stressed that resellers seeking to rely on the exhaustion defence must actively work to dispel any impression on customers that there is a commercial partnership, which UKIG had patently failed to do here.

AGA also alleged copyright infringement by UKIG in relation to a CAD drawing showing the design of the control panel for AGA's own range of electric AGA cookers. Specifically, AGA argued that by making the control panels for their eControl Cooker, UKIG had infringed the copyright subsisting in the CAD drawing on which the panel design was based. In response, UKIG attacked the subsistence of copyright in the CAD drawings on the basis they were dictated by technical considerations, and therefore, were not original.

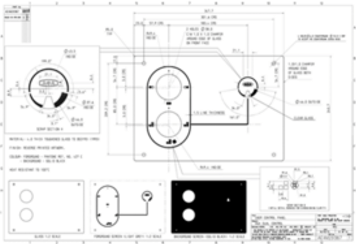

CAD drawing of the panel used on AGA’s range of electric AGA Cookers

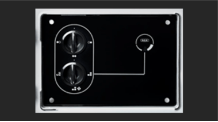

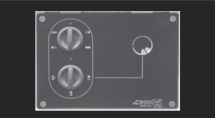

AGA Cooker control panel (top); eControl Cooker control panel (bottom)

On subsistence, the court agreed with AGA that copyright subsisted in the CAD drawing, as even where the shape of a product is, in part, necessary to achieve a technical result, the work can be still be original where sufficient creative choices have been implemented (Brompton Bicycle Limited, C-833/18). Although the control panel design was undoubtedly influenced by technical function, the designer had exercised creative freedom and made aesthetic choices which rendered the drawing original.

As to infringement, UKIG’s control panel was found to have indirectly copied a substantial part of AGA's design. However, UKIG argued it had a defence to infringement under section 51 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 ("CDPA"), which provides that an article which is made to a design will not infringe the copyright in the underlying design document, unless that design is an artistic work or typeface.

Notably, the court used this opportunity to query the status of the s.51 defence following the CJEU’s decision in Cofemel (C-683/17), which was handed down pre-Brexit and therefore remains part of retained EU law. In Cofemel, the CJEU indicated that designs can qualify for copyright protection where they meet the EU test for an original work. Furthermore, member states are precluded from limiting copyright subsistence by reference to aesthetic visual effect. By operating to limit copyright protection for non-artistic works, s.51 conflicts with the CJEU findings in Cofemel. However, in this instance, neither party had made submissions on this point. Accordingly, the court was constrained on this point and had to apply s.51 on its strict wording, finding that UKIG was entitled to rely on the defence.

Lastly, AGA argued that Mr McGinley, the creator of the eControl Panel and director with effective control of UKIG, should be liable as a joint tortfeasor. Although the trial predated the Supreme Court’s decision in Lifestyle Equities v Ahmed regarding this point, the parties were allowed to make further submissions on this issue after the judgment was handed down.

Though accessory copyright infringement was not considered due to UKIG’s successful s.51 defence, the judge nevertheless remarked in obiter that had the defence not applied, Mr McGinley could have been found liable as a primary infringer on the basis that he had authorised the would-be infringing acts by UKIG.

Regarding trade mark infringement, to be liable as an accessory, Mr McGinley had to have “requisite knowledge” of what the company was doing: namely, he must have “known the essential facts that made the act unlawful” (i.e., the act that constituted infringement). This contrasts with primary liability for trade mark infringement, which requires no such knowledge.

On the evidence before it, the court could not conclude Mr McGinley was aware that UKIG’s activities relating to the eControl Cookers would impact the origin function of AGA’s marks or give rise to a likelihood of confusion. On this basis, he did not meet the standard required for accessory liability.

This case offers both comfort and caution to sellers of refurbished products. On the one hand, refurbished products must be altered to a significant degree to give rise to legitimate grounds for a trade mark proprietor to oppose such dealings in the secondary market. On the other hand, consideration must be given to how such products are marketed and vendors must actively work to dispel any suggestion of a connection with the trademark owner, if there is none.

In relation to the copyright issue under s.51 CDPA, AGA has been granted permission to appeal this point, and we can look forward to further guidance on the interplay between copyright and designs under English copyright law, post-Cofemel.

Finally, the Lifestyle Equities v Ahmed decision sets a high bar for the requisite knowledge required to find accessory liability. In this case, the absence of any cross-examination on this point looks to have saved Mr McGinley, despite his effective control of the defendant company and the creation of the eControl Cookers. Subsequent cases will likely provide more clarity on the evidence required to establish this knowledge requirement.

Authored by Sheyna Cruz and Jackson Almond.