Trump Administration Executive Order (EO) Tracker

Search

Search

Search

Search

Blended finance structures use public capital to incentivise investment from the private sector. Historically used in the development finance and impact finance sectors, blended finance provides a way to mobilise private capital flows to plug the funding gap for climate and nature.

Different sectors and organisations define “blended finance” in different ways but there are some common structural features such as structuring the capital stack, public sector guarantees and credit enhancements and public sector grants. These are intended to reduce project risk and adjust financial returns to make projects attractive to private capital investors.

Increasing the volume of blended finance and speed-to-market requires an understanding of private sector needs and standardisation of structures and documentation.

Different sectors and organisations define “blended finance” in different ways. It is not a new concept but historically blended finance structures have been used more in the impact finance and development finance sectors. Blended Finance is simply a description of a type of structured finance that strategically uses public capital to incentivise investment from the private sector. In this article, we discuss how blended finance can be (and is) used outside the development finance and impact finance context to plug the funding gap for climate, nature and sustainable development.

Using structuring techniques to reduce the risks associated with private sector investment (which may be geographical, financial or derived from other factors) and, in some cases, enhancing the financial returns for private sector investors so that they can meet their investment criteria, blended finance applies public sector and other concessional capital (including philanthropic finance) to catalyse private sector investment.

The aim is to use the minimum amount of concessional capital to catalyse private sector investment which may not have otherwise been invested.

Blended finance not only opens up new opportunities for private sector investment but has been revolutionising public sector investment: instead of giving grants and writing-off financial assistance, the structures also provide potential for public funding returns, so that profit can be made and subsequently reinvested.

There might not be universal agreement to the definition of “blended finance” but Convergence defines blended finance in The State of Blended Finance 20241 as using “catalytic capital from public or philanthropic sources to increase private sector investment in developing countries to realise the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and climate goals. Blended finance allows organisations with different objectives to invest alongside each other while achieving their own objectives (whether financial return, social/ environmental impact, or a blend of both)”.2 The use of the term “blended finance” varies. Some require application in developing countries, others not. Some require a combination of climate and social goals to qualify, others not. Some refer only to debt, some only to equity, others a mix of the two. Different geopolitical or regional perspectives will also shape the approach to blended finance. And blended finance may be proposed to be implemented under multiple different potential structures (more on that below). So it is important to pin down the intended meaning when engaging in discussions on the subject, noting that the idea is always to combine private and public or other concessional capital in a funding structure that addresses barriers that private capital funders might otherwise face when investing for relevant purpose-driven outcomes – including high perceived and/or real risk (eg due to geographical risks and/or credit/ financial challenges and/or technological risks) and otherwise uncompetitive or insufficient financial returns.

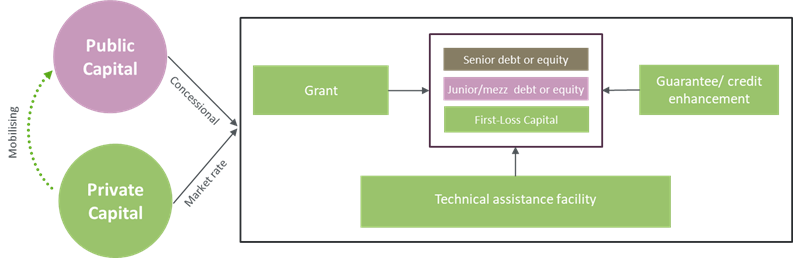

Blended finance covers a range of different structures and they are not “one-size-fitsall”. Convergence has identified four key structural archetypes,3 which are helpful to consider. Below we show them as they combine into a blended finance structure:

Figure 1: Typical blended finance structural features

Taking each of these in turn, we look at how these models work in practice, noting that structural features can be, and often are, combined to calibrate the desired risk profile and financial returns for an investment

|

Concessional or equity/first loss capital

|

This is the most frequently used type of blended finance. *including development finance institutions and philanthropic funding |

|

Credit enhancement |

Guarantees (up to 100%), insurance, contingent loans, off-take agreements or other risk-sharing mechanisms issued by, or paid for by, the public sector can be used as effective credit enhancement for projects (including to support underlying loans being made to them for financing purposes). For example, a guarantee from a third-party (generally well-known creditworthy public body), can be effective credit enhancement for a private credit provider as it offers an alternative source of repayment in the event of underlying project default. It can decrease the cost of capital for a project, meaning that private capital funding can be lent at affordable rates, without requiring any actual up-front funding by the relevant public body. As a result they are often also referred to as “unfunded” arrangements and many public and philanthropic bodies have “guarantee facilities” which provide for this type of support on a repeat, standard terms, basis. |

|

Technical assistance funding (TA Facility) |

Alongside the capital structure (whether funded or unfunded), monies are also frequently made available to provide expertise to the project to build pre- or post-investment capacity. The key here is building “invest-ability” as that also lowers credit risk of a project and so works to help attract private capital at relevant, appropriate rates. According to Convergence in September 2023, 26% of transactions had a TA component.4 |

|

Grants |

Grants may also be made – being the provision of funding into structures where there is no intention for return of the relevant amount – this may be appropriate to fund transaction design and/or pilots for example, to attract future investment from other sources. |

To understand how these features combine in action, it is helpful to consider a case study and we have set out some detail regarding the Africa Agriculture and Trade Investment Fund (AATIF) below:

AATIF is a blended finance vehicle which invests in businesses along the agricultural supply chain. The fund’s aim is to “increase food security, strengthen income among people employed in the agricultural sector, and strengthen the competitiveness of local agriculture businesses”. DWS manages the fund and provides direct finance to commercial farms, processing companies and cooperatives, and invests in financial institutions and large agricultural intermediaries on-lending to small and medium companies.5

Fund characteristics:

See here for more detail about the AATIF.

Although blended finance is not a new product, it is not mainstream yet. Transactions remain complex and bespoke, often with many negotiating parties who have conflicting expectations and documentary requirements. Consequently, transactions can take a long time to arrange, increasing cost and reducing its use. And a lack of commonly accepted terms and documentation makes it more difficult to scale blended finance to achieve the volumes needed.

For example, in emerging/developing economies in the Asia-Pacific region, the drive towards meeting the Sustainable Development Goals and other climate change mitigation and adaptation goals can involve the education and co-operation of multiple parties and stakeholders, across both private and public sectors.

Private capital investors require transparency and accountability assessments, including whether blended finance projects have adequately complied with their social, environmental or nature goals, which need to be implemented and monitored regularly. These bespoke requirements and structures require time, co-ordination and cost, which can impact commercial assessments of risk and return and could result in traditional/ mainstream providers of capital and global financial institutions being reluctant to finance blended finance structures, instead opting for more well-established financing structures.

Ravi Menon, Singapore’s Ambassador for Climate Action & Senior Adviser (National Climate Secretariat) also identified similar barriers in his speech on 12 September 2024 at Unlocking Capital for Sustainability 2024 that Asia’s transition financing needs are large but private capital is prevented from flowing to Asia due to:

In addition to the market challenges for blended finance discussed above, there are also regulatory challenges in this space. Parties have to navigate an increasingly complex regulatory perimeter affecting blended finance. Regulations such as the EU Alternative Investment Fund Management Directive and the EU Securitisation Regulation (and UK Securitisation Regulation) pose compliance issues for some arrangements. Many investors have policies which prohibit investment in securitisations for example, or are subject to risk capital and liquidity rules that make blended finance investments unattractive, despite the obvious sustainability benefits and practical risk adjustment features being offered.

A regional or jurisdictional regulatory regime conducive to blended finance, for example with beneficial securities, trusts or insolvency law regulations as they pertain to blended finance structures, will be beneficial in encouraging more widespread adoption.

In addition, the tax system in many jurisdictions is designed for entities which are either not for profit or for profit – whilst blended finance structures often fall between the two. Even when regulatory and tax issues for a transaction are resolved for one set of investors, the addition of new groups of investors may entail structural acrobatics with multiple vehicles (potentially across a number of jurisdictions) and further differentiated terms, in order to bring everyone into the same deal. In this context, common pathways to “getting the deal done” including agreed arrangements on documenting level of impact/outcomes, financial reporting and compliance features, technical metrics, straightforward accommodation of multiple bespoke “investment policies and exclusions”, governing law and jurisdiction, acceptable credit ratings and due diligence processes, would be of significant value to sponsors and structurers (and as a result, ultimately to project beneficiaries, who will be able to access larger amounts of less conditioned capital at appropriate prices).

With commonality and consensus, the efficiency could translate to a quicker return-on-investment horizon and thus presents a more attractive investment opportunity for private sector providers of capital.

There is evidence of a stronger governmental focus on blended finance, with the UK announcing the National Wealth Fund, designed to deploy catalytic capital to invest in five priority sectors: green steel, green hydrogen, industrial decarbonisation, gigafactories and ports. The UK Transition Finance Market Review also refers to the importance of blended finance.On 12 September 2024, Singapore’s Ravi Menon revealed Singapore’s blended finance platform “Financing Asia’s Transition Partnership” (FAST-P) which targets the areas which it identifies as “most pertinent to Asia’s transition” under three themes:

This initiative, with a target fund size of US$5bn, aims to utilise blended finance to play a significant part in bridging the energy transition financing gap across Asia-Pacific, with the increased adoption of concessional capital, the involvement of the multilateral development banks to provide technical expertise as well as regional financial institutions providing de-risking mechanisms and risk mitigation solutions for blended finance transition projects.

These are recent examples of governments embracing blended finance and we can expect to see much more from governments recognising the need to support blended finance markets.

This article was first published in the November 2024 issue of Butterworths Journal of International Banking and Financial Law.

Our global Sustainable Finance & Investment group brings together a multidisciplinary global team that provides clients with best-in-market support. We are following the development of ESG regulation in the UK, the EU and globally closely so please get in touch if you would like to discuss.

This note is intended to be a general guide and covers questions of law and practice. It does not constitute legal advice.

The market for blended finance in the climate and nature context remains nascent. Therefore, we can expect teething issues whilst participants focus on scaling a few structures which will become standard when the private and public sector participants find more common ground on terms, taxonomies and practices which are suitable for them all.

Blended finance is one of a number of available financing and investment tools for channelling capital into climate and nature, with some particular features that make it appropriate for leveraging “mixed purpose” outcomes (which combine environmental and social or community features, for example) and also developing country applications, which might not otherwise be commercially investible at appropriate pricing. The risk-mitigation techniques within blended financing structures will encourage private sector involvement and help to address the perceived lack of available risk capital. It is set to become an increasingly important way to mobilise private sector funds to mitigate and adapt to climate change and finance conservation and restoration of nature.

References