Reflecting on President Trump’s first 100 days in office

Search

Search

Search

Search

The International Energy Agency released a report this week titled “The Path to a New Era for Nuclear Energy” (the “Report”), which looks at opportunities for nuclear energy to meet rising energy demand, while addressing energy security and climate concerns. The Report also looks at the critical elements to pursue these opportunities—including policies, innovation, and financing.

The International Energy Agency (“IEA”) Report explains that nuclear energy is experiencing a resurgence, driven by rising investments, technological advancements, and supportive policies in over 40 countries. With electricity demand projected to grow, particularly from data centers, stable low-emissions energy sources are increasingly vital. Despite this momentum, challenges in policy, construction, and financing remain. The Report, therefore, examines the global status of nuclear energy, its long-term outlook, and the investments needed through 2050. It also highlights how innovation, government support, and new business models could further enable small modular reactors to shape a new era for nuclear power.

We provide a high-level summary of the Report, which also includes a number of useful graphics, below.

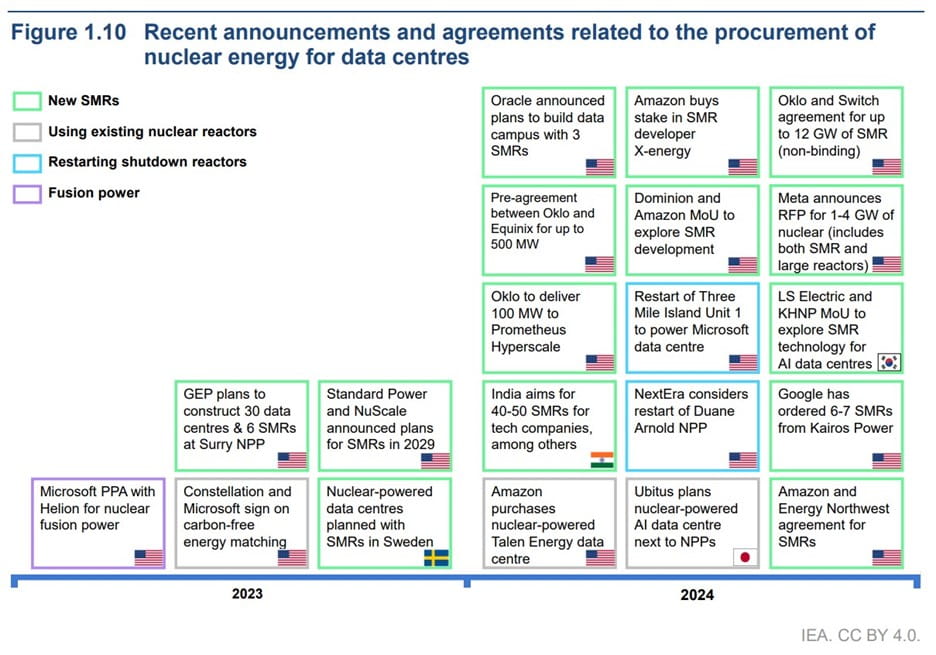

Lay of the land: nuclear has huge potential to grow

As the world’s second-largest source of low-emissions electricity, nuclear energy is currently seeing unprecedented growth. As the IEA notes, nuclear energy is set to generate a record level of electricity in 2025. Report at 8, 15. In addition, more than 70 gigawatts of new nuclear capacity is under construction around the world, and more than 40 countries are looking at deploying new nuclear. Report at 8. This thirst for new nuclear is driven in part by rising energy demand—in markets like the United States, from data centers (as we have written about), global electrification, and broader development within emerging economies—as well as dual concerns about decarbonization and energy security. Report at 25, 37-39. Nuclear is uniquely qualified to meet these needs because it provides reliable, clean, baseload power—meaning it can power a data center or a regional grid 24/7 without emitting greenhouse gas emissions. And the unique attributes of nuclear energy have made it particularly attractive to meet the surging data center energy demand, with a number of high-profile announcements in this space, particularly in late 2024. Report at 38, Figure 1.10 (below).

Innovation is also driving the momentum for new nuclear projects, according to the Report. Small modular reactors (“SMRs”) are drawing increased interest from the private sector. Data centers alone are projected to account for up to 12% of U.S. electricity demand by 2028—the result being that in the United States, data centers are emerging as a “dedicated market” for nuclear energy, including SMRs. Report at 37. Globally, expansion of electric vehicles and wider adoption of high-energy appliances like air conditioners will transform regional grids. Report at 37. SMRs are well-suited for these needs. SMRs, which are anticipated to be quicker to build, could realize greater cost reductions compared to large reactors through nth-of-a-kind deployment, especially if major portions of SMRs can be built off-site in a modular system, thereby offering significant efficiency gains. Report at 47. With consistent support of SMR innovation and deployment, a total of 120 GW of SMRs could be deployed globally by 2050. Report at 47. The United States is at the forefront of SMR development and is expected to remain so through 2040—meaning all eyes are on us to properly support and develop these vital technologies.

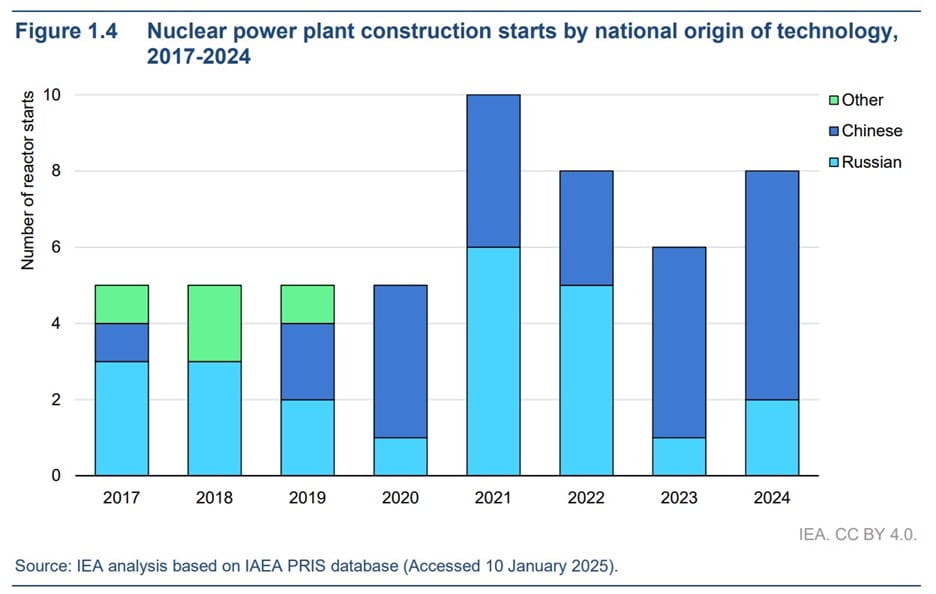

Global interest, but regional momentum

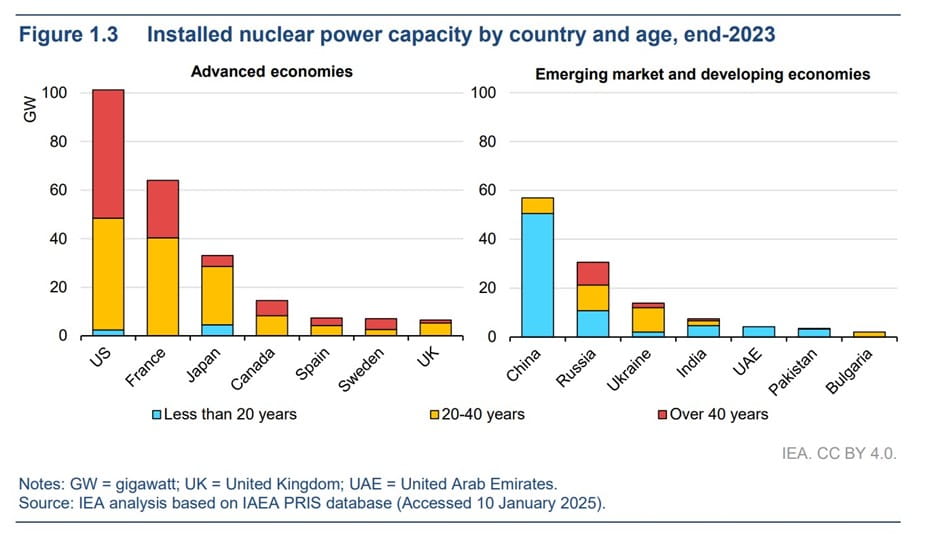

As the IEA points out, though, the global map in nuclear leadership is not what it used to be. Half of the nuclear reactor projects under construction today are in China, which now has the third-largest nuclear fleet in operation in the world. Report at 14, 19. Additionally, Russia is the leading exporter of nuclear technology, with projects in emerging and developing countries around the world using Russian technology. All in all, the vast majority of nuclear reactor construction projects underway today are fundamentally Chinese or Russian. Report at 20-21. Starting in the 2030s, emerging markets and developing economies—most of whom are currently reaching for Chinese or Russian designs—will become hubs of nuclear reactor construction, creating possibilities for other countries to step in with project support. Report at 19, 57, Figure 1.4 (below).

By contrast, while most of the world’s operating nuclear reactors are in advanced economies—mostly in the United States and European Union—those reactors are aging, meaning many will need to either shut down or undergo lifetime extension projects in order to keep operating. Report at 14, 19, and Figure 1.3 (below).

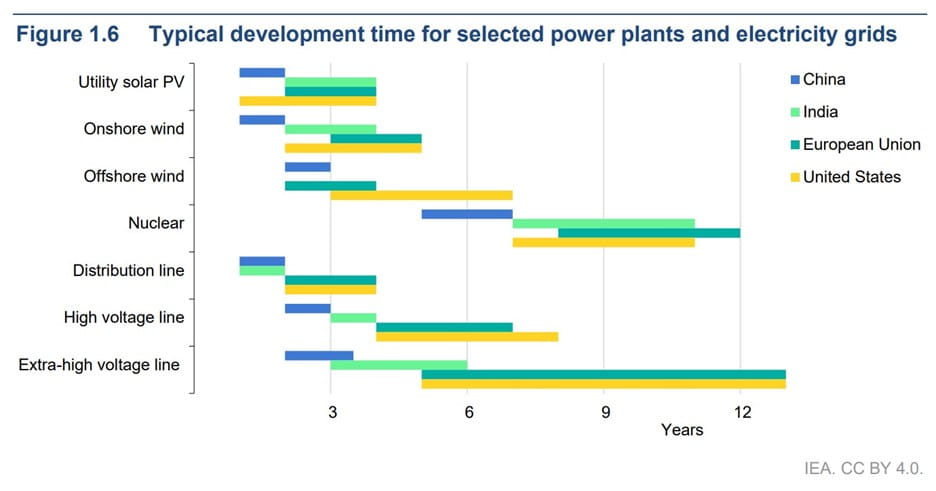

New nuclear plants also take longer to build in advanced economies, with many recent projects in the United States, Europe, and Korea experiencing significant delays. Report at 22-23. Construction time has a direct impact on total project costs—delays in bringing a new plant online lead to cost overruns, which the U.S. Department of Energy studied from a U.S. perspective in its most recent Liftoff report (written about here). Report at 22-23. These delays are especially costly for an industry that already takes longer to deploy than other forms of energy because of their larger size, the complexity of nuclear technology, and stricter regulations. Report at 22. In fact, the IEA notes that the prospects for the nuclear industry depend on whether reactors can be built on time and on budget. Report at 52 and Figure 1.6 (below).

So how do we deploy more nuclear?

By realizing that a new era in nuclear energy will require a lot of investment. To take advantage of these opportunities, governments must be prepared to provide a consistent strategic vision—avoiding the “stop and go” cycles that deter major supply chain investments—alongside a stable regulatory framework that will provide the private sector with the confidence to invest. Report at 62-63, 66-67. Some of the unique considerations of nuclear can add additional costs, such as from “backfit requirements” mandating operators to upgrade retrofit facilities; accident risk; and managing the back-end of the fuel cycle through reprocessing and/or long-term storage. Report at 72-73.

In terms of financing, the biggest risks come from the construction phase. Governments can especially help by de-risking nuclear projects in order to facilitate the involvement of commercial banks, such as by ensuring predictable cash flows or taking on some of the construction risk. Report at 69. In markets with volatile prices, de-risking instruments such as long-term power purchase agreements, contracts for difference and regulated asset base models are indispensable. Report at 11. In less-developed energy markets, government-backed Export Credit Agencies can offer credit insurance in collaboration with multilateral development banks, offering credibility and security to nuclear projects. Report at 85.

Most importantly, though, the private sector will have to step up, which means near-term nuclear projects will have to deliver on-time and on-budget. Report at 86-87. The private sector increasingly views nuclear energy as an energy source ripe for investment, especially for energy-intensive operations like data centers and electrification.

Financing tools can help de-risk these investments—cash flow predictability is key. For instance:

Other solutions suggested by the U.S. Department of Energy in its most recent Liftoff report (which we summarized here) include mitigating the risk of cost overrun through sharing costs or deploying different contractual or credit tools.

Additionally, for advanced economies, SMRs have major potential to bring in new investors and end-users—thereby expanding the use of nuclear energy. SMRs are designed to be smaller, more flexible, less complex, and hopefully see more streamlined regulations, reflective of their lower risk profile. While the IEA projects that SMRs could have higher per-unit construction costs than large reactors, their smaller overall investment makes them attractive, particularly to private financial institutions who regularly finance comparable projects—and in IEA’s projection, both SMRs and large reactors are cost-competitive with other sources of generation. Report at 54, 95. The IEA predicts that if the first wave of SMRs are delivered on-time and on-budget, their lower costs—which are easier for private lenders to finance—could unlock a wave of new private investment in nuclear energy. Report at 95.

The next decade will be critical for setting up the nuclear industry to meet its full potential. Stable governmental support and increased private investment—and of course, early projects delivering on-time and on-budget—all have roles to play in helping expand deployment of this critical technology.

For more information, please contact Amy Roma, Partner, Stephanie Fishman, Senior Associate, or Cameron Tarry Hughes, Associate.