Reflecting on President Trump’s first 100 days in office

Search

Search

Search

Search

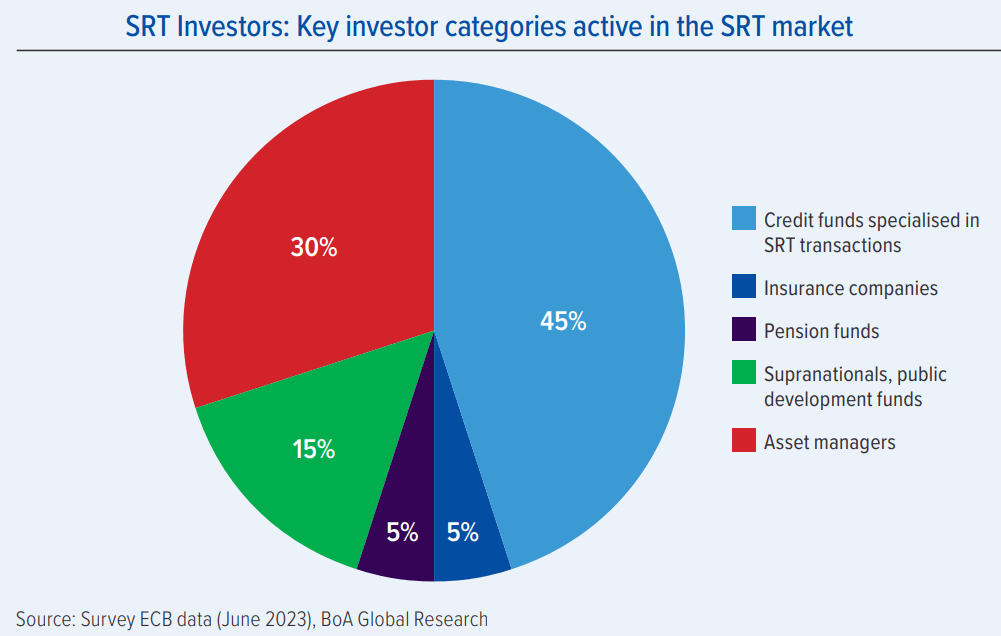

The growth of balance sheet risk transfer within Europe shows no signs of abating. The ability to utilise "significant risk transfer" or "SRT" (at it is more commonly known in the EU and the UK) allows banks to deploy locked up regulatory capital to further their lending portfolio. This is achieved by transferring the credit risk in the loans, but not the loans themselves, to institutions such as hedge funds, insurers or asset managers which are not currently burdened by prudential regulatory capital requirements.

The implementation of Basel III represents a critical moment for global financial regulation, fundamentally altering the landscape for securitisation markets. As jurisdictions navigate the complexities of aligning with the framework, divergent approaches in the EU and the UK are creating distinct challenges and opportunities for market participants.

This has brought the SRT market into sharp focus. Regulatory capital requirements such as the supervisory parameter and the output floor are not just reshaping the economics of securitisations but also driving innovation in structuring and risk allocation. Meanwhile, insurers remain in our view a key untapped resource in this space, held back by restrictive frameworks and counterparty risk considerations.

Against this backdrop, this article explores the latest developments in the SRT market in Europe, examines their implications for key stakeholders, and looks ahead to the trends likely to define 2025.

The global financial crisis exposed critical vulnerabilities in the banking sector, prompting swift action from the Basel Committee for Banking Supervision (the "Basel Committee"). In November 2010, they unveiled the original Basel III standards, laying the groundwork for a series of amendments culminating in the final Basel III framework in December 2017 ("Basel III"). This comprehensive overhaul aimed to curb excessive variability in risk-weighted assets ("RWAs") and enhance comparability between supervisor-approved internal models and the standardised approach.

The initial implementation date for Basel III was set for 1 January 2023. However, this timeline was postponed due to disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Additional delays arose in various jurisdictions as regulators addressed practical challenges and concerns associated with some of the more extensive implications of the proposed legislative measures.

Current state of play:

The ongoing implementation of the Basel III framework is having a profound impact on the significant risk transfer industry. On a direct level, the regulatory capital treatment of synthetic on-balance sheet securitisation positions and the treatment of first-loss tranches and synthetic excess spread affect both originators and investors in the SRT space. Indirectly, measures such as the output floor (a minimum threshold for risk-weighted assets calculated using internal models) may also drive changes by incentivising banks with ever-higher capital charges for un-securitised portfolios to explore economically viable strategies for transferring credit risk. Please see our earlier article on the benefits of significant risk transfer and some of the main legislative background.

We consider below 7 key issues impacting the market and what's in store for the SRT market in 2025.

Although most national competent authorities in the EU have adopted and accepted the use of unfunded credit protection for SRTs, the PRA had not previously permitted the use of unfunded credit mitigation in synthetic securitisations. However, there has been a welcome warming to the position in the UK Consultation, where the PRA stated (acknowledging that this was already commonplace in the EU) that in principle it should be possible for originator institutions to use unfunded credit protection for achieving SRT.

The PRA did note that such transactions could have "complex features" which would need to be discussed on a case by case basis, with the key risk being a downgrade of the protection provider (and the consequential stress-testing to be done by the originator to ensure that it had alternative arrangements in place in such circumstances).

A significant discussion point for investors and originators in the securitisation industry is the existence of the so-called "non-neutrality factor", captured in the capital equation through the supervisory parameter "p". The supervisory parameter is a premium charge payable for securitisation transactions that is intended to reflect the modelling and agency costs associated with securitising an exposure. This has come under renewed focus as a result of STS treatment (which decreases the supervisory parameter) and the introduction of the output floor (which brings into focus the supervisory parameter under the standardised approach even for banks that have previously relied on internal models to decrease their RWAs).

In the EU, in order to ensure that the output floor does not have a cliff edge effect, a temporary halving of the supervisory parameter (until 31 December 2032) has been implemented. Meanwhile, a more permanent solution has been proposed in the UK Consultation, allowing SEC-SA banks to use some of the flexibility in the IRB supervisory parameter calculation to achieve a lower supervisory parameter.

At present, while both the UK Consultation and the EU Consultation acknowledge ongoing efforts to review data and assess the impact of the newly implemented rules, further relaxation of these regulations does not appear to be a development likely to occur in the near term.

The European Banking Authority ("EBA"), in its Report on Significant Risk Transfer in Securitisation under Articles 244(6) and 245(6) of the CRR (published in 2020), proposed that national competent authorities run significant risk transfer and commensurate risk transfer tests as part of the initial SRT assessment (i.e. prior to origination of the transaction), without having to rerun the tests on an ongoing basis (unless there was incomplete or missing information provided with the original assessment, or a significant change such as a restructuring to the transaction). This does not seem to have been picked up by the PRA, potentially exposing originators to cliff edge effects when these tests are re-administered. Greater clarity on this issue from both the PRA would be highly beneficial.

The PRA will retain its discretion to assess, on a case by case basis, whether significant credit risk has been transferred to third parties where the possible reduction in RWAs (which would be achieved through the securitisation) is not justified by a commensurate transfer of credit risk to third parties.

In addition, the ECB has developed a fast-track process for the supervisory assessment of SRT transactions, which is aimed at decreasing the current 3-month time period for approvals. This process is expected to be tested during the first half of 2025, and if successful would lead to a more efficient SRT process for European banks, particularly for those with more established programmes and a more commoditised product.

Under the CRR, originators are permitted to cap their SEC-SA or SEC-IRBA securitisation position RWAs by reference to the underlying exposures which have been securitised (i.e. had they not been securitised). This is possible by applying a look-through approach for senior securitisation positions, as well as an overall cap (for all securitisation positions held by the originator).

For the overall cap calculation, this may be done by multiplying the RWAs under the usual SEC-SA or SEC-IRBA approaches by the largest proportion of interest (calculated as the nominal value of such tranche held by the originator over the aggregate nominal value of the tranche) which the originator held in the relevant tranche(s) (being the "V Parameter"). This means that if the originator retained 100% of the first loss tranche, even if such first loss tranche represented only 5% of the notional value of the entire securitisation, this cap (being, in this example, 1,250%) would apply to all tranches held by the originator and therefore make it redundant. The Joint Committee Advice (Banking) recommended carving out from the calculation any tranches to which the originator applied a 1,250% risk-weighting or which was deducted from their CET1 calculations – which economically speaking would capture most first loss tranches held in this manner.

The UK Consultation has proposed a further and more flexible calibration. This allows originators to modify the cap calculation to exclude certain portions of tranches from it, and then add those portions back in at their exposure value. This would apply not just for 100%-retained tranches, but any tranche (depending on the percentage value set by the originator for the calculation).

An alternative way for originators to achieve regulatory capital benefit is through accounting derecognition transactions. Provided the criteria under IFRS 9 are met, originators may achieve full accounting derecognition in true sale securitisations, and thereby decrease the "exposure value" of the relevant securitised assets. The exposure value is used for the basis of determining RWAs under the CRR, so having a fully derecognised asset would mean that the originator no longer has to hold any RWAs in respect of such exposures (notwithstanding that they may remain lender of record for such assets). This can be an attractive alternative to SRT transactions, given no SRT tests are required to be met and (generally) no regulatory approval is required.

It remains to be seen whether such transactions become more prolific. The use of derecognition transactions carry certain limitations, including potential accounting recharacterisation in respect of portfolios on their P&L.

Given the nature of SRT transactions, the majority of legislative developments relate to the protection buyers' regulatory capital position. However, protection sellers continue to play a fundamental role in the development of the SRT markets, both in terms of structuring transactions and providing the know-how for less experienced SRT protection buyers. Protection buyers typically view their SRT transactions as a partnership whereby they share exposure to their core lending products, with the protection sellers providing regulatory capital relief.

Some of the developments in the SRT space will result in a changing landscape for protection sellers: an increase in RWAs as a result of the output floor could result in a demand for thicker mezzanine tranches to make transactions economically viable, while an inability to rely on STS designation in the UK may result in more privately rated SRT transactions. Meanwhile, the diverging landscape between the UK and the EU may mean that certain structural features, such as synthetic excess spread (which is subject to much wider regulatory capital derogations in the EU than in the UK) and call options will have to be tailored to specific jurisdictional needs.

Since April 2021, the EU has allowed synthetic on-balance sheet securitisations to be afforded the preferential prudential treatment under the simple, transparent and standardized or "STS" designation. This was a complete game changer for banks using the standardised approach to calculate RWAs, which now benefit from lower risk-weight floors on their retained senior tranches and therefore a reduction in the size of the mezzanine tranche which they are required to place in order to receive beneficial capital treatment.

The UK has not followed this approach and the market is bifurcated, as the PRA remains resistant to extending the STS label, as most recently indicated in the UK Consultation. This means that UK banks and credit institutions may not avail themselves of the beneficial treatment enjoyed by their EU counterparts.

A key consideration both in the UK and the EU is the continued expansion of insurers as protection sellers (whether directly or, when carefully structured (as discussed below), indirectly).

On 12 December 2022, the Joint Committee of the European Supervisory Authorities and the European Securities and Markets Authority delivered advice on the review of the securitisation prudential framework from an insurance perspective.

The general view and responses from market participants suggested that the introduction of the Securitisation Regulation had no major impact on the investment decisions of (re)insurers, with only 12% of standard formula (re)insurance undertakings having any investments in securitisations, and with 60% of those investing less than 1% of their total investment assets in securitisations.

Recent revisions to the Solvency II frameworks in both the EU and the UK may present an opportunity for reduction of insurers' overall capital requirements. As an example, in the UK, the widening of the matching adjustment rules to permit assets with highly predictable cash flows (rather than the previous fixed cashflow requirement) to be included in matching adjustment portfolios could increase insurer appetite in these markets. However, these reforms primarily focus on broader regulatory adjustments rather than explicitly incentivising insurers to increase their involvement in securitisation markets.

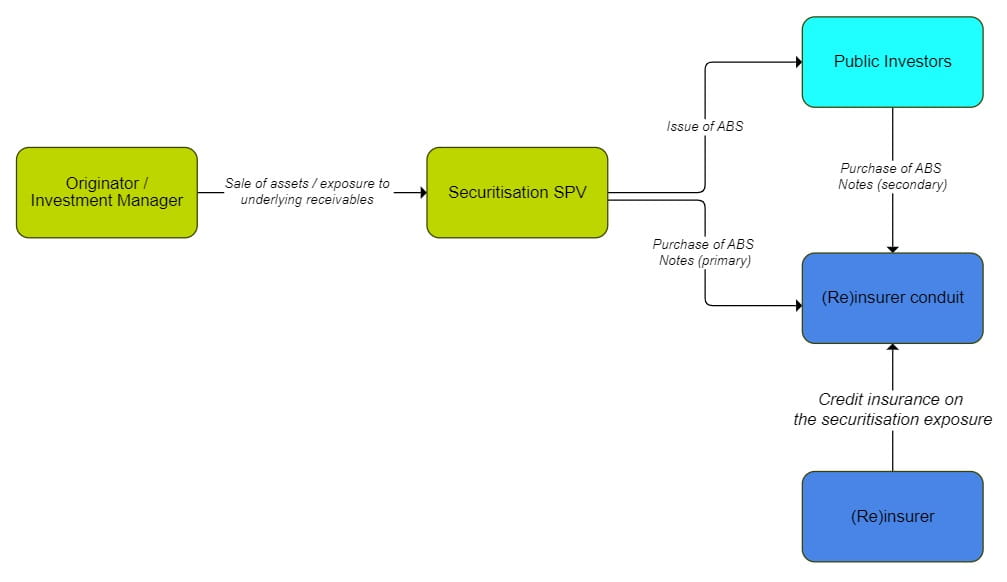

In the securitisation space more generally, it may continue to be more attractive for insurers to gain indirect exposures to the cashflows of a securitisation, given the higher regulatory capital burden for a direct investment. A simplified structure for the indirect exposure is set out below:

In the SRT space, where there are longer-dated assets, investment may be more attractive for insurers: because it would allow insurers to match the longer-dated asset (the ABS Notes above) with their own longer-dated liabilities and better align with their risk and liquidity appetite. Further, notwithstanding the limitations of insurers acting as protection providers (particularly in the case of funded synthetic securitisations), insurers may still participate in such structures through back leveraged transactions, whereby a bank or other credit institution acquires (or funds the acquisition of) a credit-linked note on behalf of the insurer, who would then provide a CRR-compliant financial guarantee (or insurance policy) and then receive the pass-through cashflows from the CLNs directly. Any such financial guarantee or policy of insurance could be further mitigated by syndication, for example through a reinsurance treaty.

However, despite the large amount of capital which can be deployed by insurers, their involvement in the SRT space remains limited.

This could be attributed to a number of reasons:

The evolving landscape of the Basel III implementation and its associated regulatory frameworks in the UK and the EU continue to reshape the securitisation market and SRT markets, with significant implications not just for banks and insurers, but also non-prudentially regulated entities such as asset managers that participate in such structures. Although the ECB has expressed concern about leverage and interconnectedness in the SRT market (particularly where banks are involved on a sell-side structure), the regulators have been aligned in acknowledging the importance of SRT in the ability of banks to manage their capital requirements.

In the EU, the proactive stance on STS treatment for synthetic securitisations has provided a pathway for standardised banks to optimise capital efficiency, although for SEC-IRBA banks, only a temporary halving of the supervisory parameter was offered. In the UK, significant efforts have been made to maintain the competitiveness of UK banks, although the regulators remain cautious about the extension of STS treatment to synthetic securitisations. Developments in the insurance regulatory capital regime under Solvency II may potentially act as a catalyst for further (re)insurer engagement, although these changes will need to be matched by equivalent changes for the banking regime to ensure no disjunction is created, particularly in the SRT space.

As we go through 2025 and the ever-increasing quest to manage risk effectively, the SRT market stands at a crossroads: achieving the balance between financial stability, market efficiency and cross-jurisdictional competitiveness will remain critical for the continued growth and resilience of the sector, as well as the benefits such sector provides to the wider economy.

This note is for guidance only and should not be relied on as legal advice in relation to a particular transaction or situation. Please contact your normal contact at Hogan Lovells or any of the authors if you require assistance or advice in connection with any of the above.

Authored by James Doyle and George Kiladze.